The Permian-Triassic mass extinction was the most severe biodiversity crisis in Earth’s history, with an estimated 90% of species disappearing. Occurring approximately 252 million years ago, it marks the boundary between the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras.

The Permian-Triassic is perhaps the clearest example in the fossil record of a “greenhouse” extinction, associated with the eruption of a massive volcanic province in Siberia and rapid warming of the planet’s surface, accompanied by sluggish ocean circulation, rising sea level, and anoxia in many marine environments. My work has focused on how these oceanographic changes affect the base of the marine food web: the inorganic nutrients and planktonic algae that ultimately support a complex fauna.

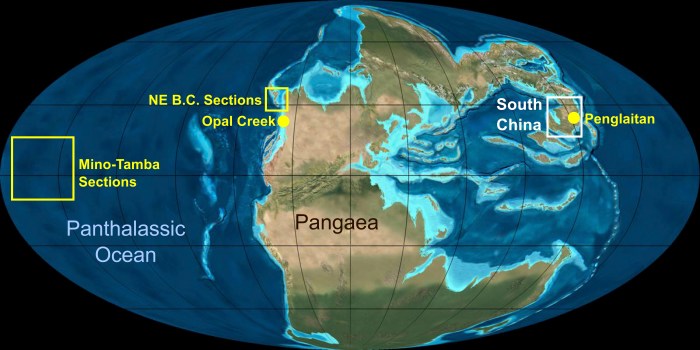

The oceans of the Permian and Triassic were not a single environment, any more than the ocean is a single environment today; warm, clear waters supporting carbonate reefs coexisted with cool, productive upwelling zones. Shallow, sunlit epicontinental seas and permanently dark abyssal plains were both impacted by the extinction. The reorganization of ocean currents and chemistry across the Paleozoic-Mesozoic transition was spatially complex, and to fully understand it, we need to take the approach of explorers, filling in the empty spaces on the map.

I’ve focused mainly on the Panthalassic, a deep, open ocean basin that dwarfed even today’s Pacific. While it was the largest ocean on Earth at the time, Panthalassic sediments of Permian-Triassic age have only been preserved in a few places, with the Canadian Rockies and Mino-Tamba terrane of Japan containing some of the best exposures. I’ve also had the chance to get involved in work on Penglaitan, a shallow-water section in southern China that may be our highest resolution surviving record of the latest Permian.

Opal Creek: The Opal Creek section, in the Kananaskis Valley west of Calgary, was deposited in an outer shelf setting on the northwestern margin of Pangaea. Opal Creek was located in a cool, highly productive upwelling system that supported a reef-building siliceous sponge fauna until it was terminated by weakening circulation and increased sedimentation at the Permian-Triassic boundary. Since the Opal Creek upwelling system was first described (PDF, PDF), Opal Creek has become the best-studied Permian Triassic boundary section in North America (see LINK), and is used to field test newly-developed isotope systems such selenium (PDF), multiple sulfur isotopes (PDF), thallium (PDF).

Northeastern British Columbia: Two sections from the Williston Lake area in northeastern British Columbia, Peck Creek and Ursula Creek, provide a glimpse of the western Pangaean upwelling system at a higher latitude. These sections have a similar sequence of facies to Opal Creek, with a transition from biogenic cherts to organic rich siltstones and shales at the Permian-Triassic boundary and distinct pyritic horizons in the extinction interval (PDF). Ongoing studies in British Columbia focus on Cache Creek Terrane and the Montney Formation.

Penglaitan, Guangxi, China: The Penglaitan section, located on the Hongshui River outside of Laibin, is an unusual and fascinating record of the latest Permian. Penglaitan experienced extremely rapid sedimentation in the final 200,000-300,000 years of the Permian – the section contains over 600 meters of marine sediments in the late Changhsingian, as well as the final known terrestrial flora of the Paleozoic. This high temporal resolution allows us to recognize the suddenness of the event (PDF). The section and an associated core are also the subject of redox (PDF) and isotopic studies.

Mino-Tamba terrane sections: The Mino-Tamba terrane is a succession of bedded radiolarian cherts deposited at equatorial latitudes in the abyssal Panthalassic ocean. Having been accreted to Japan, these sediments are a unique window into the Permian and Triassic ocean free from the influence of nearby continents or sediment sources. I have generated organic carbon and nitrogen isotope datasets for two of these sections, Ubara and Gujo Hachiman, that have been incorporated in studies of the greenhouse nitrogen cycle (LINK).